(1) Manages Professional Tasks and Responsibilities

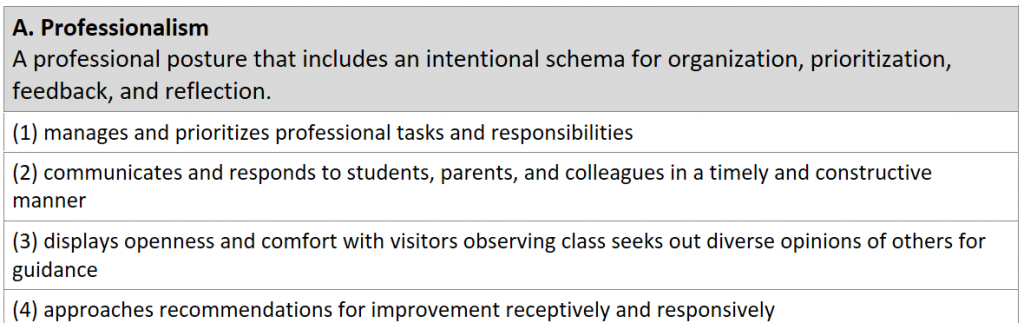

Given that there are so many different aspects of my work at EPS, I spend a lot of time writing down and deciding how to prioritize my professional tasks and responsibilities. This year, my roles include middle school technology teacher, makerspace manager, PDP candidate, robotics coach, and EBC week trip lead. Having so many roles and responsibilities, coupled with my ADHD which complicates time management on its own, has pushed me to the limit of what I felt I could handle on many days. One strategy that helps me is writing to-do lists.

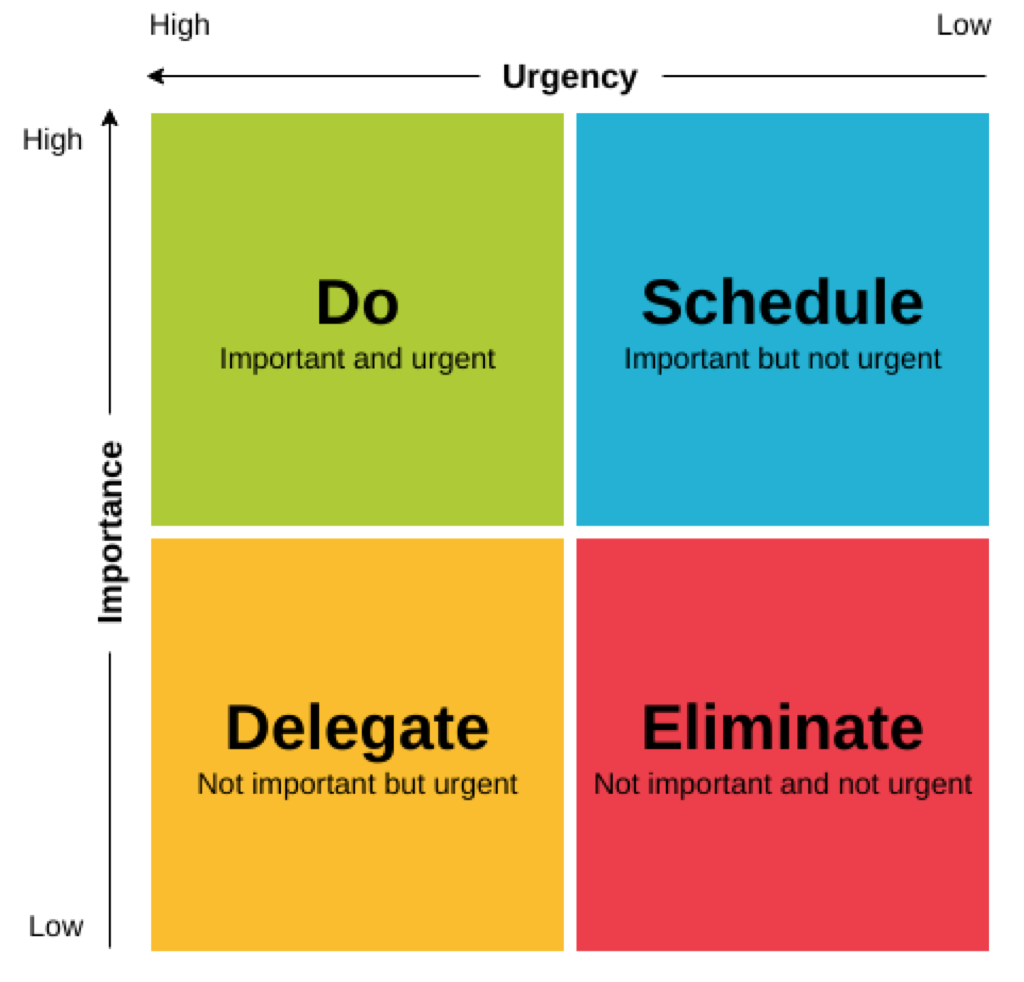

The to-do list above is separated by the different roles and responsibilities I have this year. When I make a list like this, I don’t prioritize the items by importance, but simply by whichever task comes to mind first. Then when I have everything I need to do out of my brain and on paper, I first want to cry because it’s a LOT for my neurodivergent brain to process, but then I organize the list items in a way that helps me prioritize and complete them. My preferred method for this is called the Eisenhower Matrix.

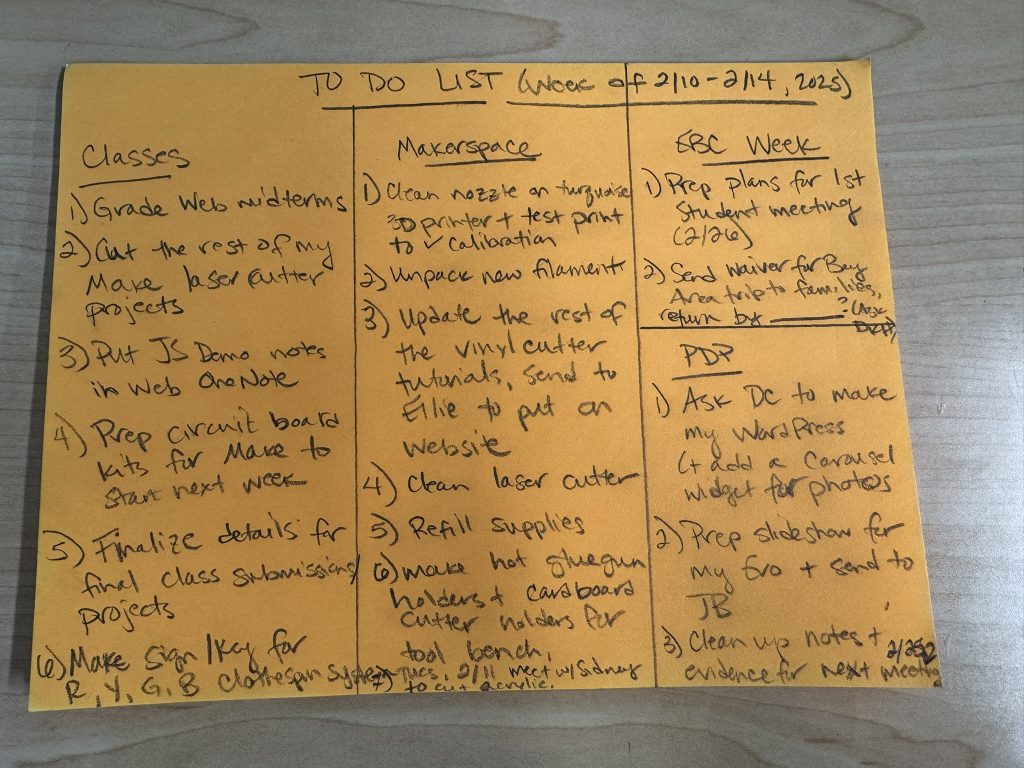

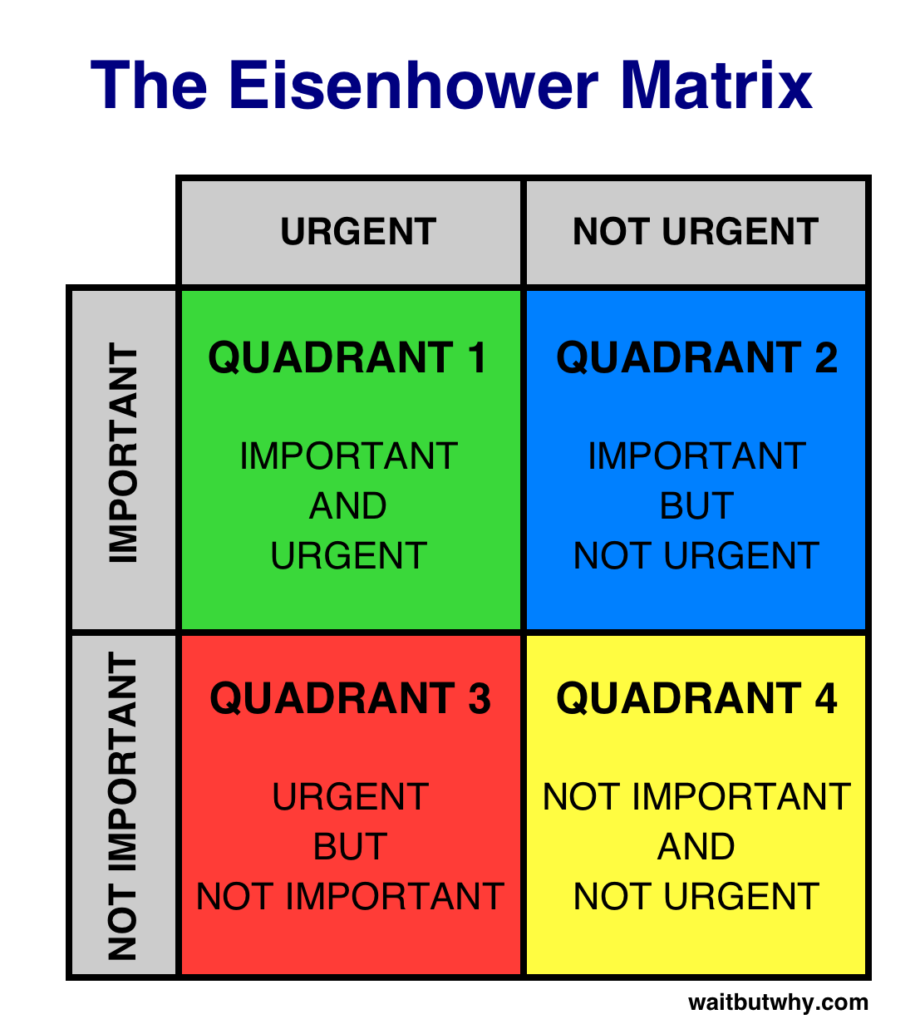

The Eisenhower Matrix was shared with me by Kip Wassink several years ago when my job became more complex after my duties were split between teaching classes and managing the makerspace. I was struggling to find a way to decide what order to complete my tasks so I could get things completed in a timely manner, so I reached out to Kip for advice. The photo below shows what my to-do list from above looks like organized into the Eisenhower Matrix.

Once my tasks are organized and prioritized in this way, I can clearly see what needs to be done, plan for when to do them, and decide if some of the things on the list can be done by someone else (delegated) or if they need to be done at all (can I eliminate them?). This decision-making process is shown in the chart below.

I will do all of the green’s immediately, schedule a time to do the blue’s later, delegate what I can in the yellow’s (especially if some things can be given to a student to do for me), and either eliminate the red’s or save them for when I am experiencing to-do list fatigue. For my example to-do list above, I graded my web midterms and prepped the slides for my Evolution of Instruction presentation immediately after organizing my list (green). I made a meeting request with myself for the following day to cut the rest of my MAKE projects and clean the laser cutter (blue). I asked a student for help packing the circuit board kits for MAKE and to refill supplies on the materials library (yellow). Finally, I allowed myself time for a creative task (red) because I was feeling to-do list fatigue. Some would say anything in the red quadrant should be eliminated, but my secret is to save these items for when I want a task that is either fun or low-stakes or a personal project. Anyone who knows me is well aware I could spend all day every day making things, so I prevent myself from getting lost in a hyperfocus state by setting a timer for how long I’ve allotted myself to do the task. Most recently, the red tasks I’ve been doing have been decorations for my kids’ birthday party. Sometimes these items are seen as time-wasters in the Eisenhower Matrix, but I personally find them necessary and helpful when I need a brain break! Plus, I’m honing my maker skills for the makerspace side of my job, right?…

Effectively managing a wide range of professional responsibilities requires intentional organization, flexibility, and self-awareness. By using tools like the Eisenhower Matrix and leaning into strategies that work for my neurodivergent brain, I’m able to prioritize tasks, meet deadlines, and stay present for both my students and colleagues. Balancing structure with grace—especially during times of overload—has helped me sustain my energy, maintain high-quality work across all roles, and model practical executive functioning strategies for my students.

(2) Communicates and responds to students, parents, and colleagues in a timely and constructive manner

My classroom is a busy place and I have students and adults in and out constantly, so finding time to read and respond to emails is something I have had to build systems around to manage. In the past, I spent time at home each evening to work on my inbox if I wasn’t able to during the day, but now that I have two young children who need my attention, this is a practice I have had to abandon. I am clear up front on my syllabus and at parent night that students and parents should not expect me to reply to emails after 4:00 pm.

The new system I have in place for emails takes place most mornings once I arrive at school. I aim to arrive by 7:30 am, which gives me 15 minutes before any morning meetings and before students enter the building, for quiet time to check emails and respond. If this doesn’t happen for traffic or whatever other reason, I set aside time during middle band to work on emails. I am not an advisor, so I have time when students are engaged in advisory activities to work on emails.

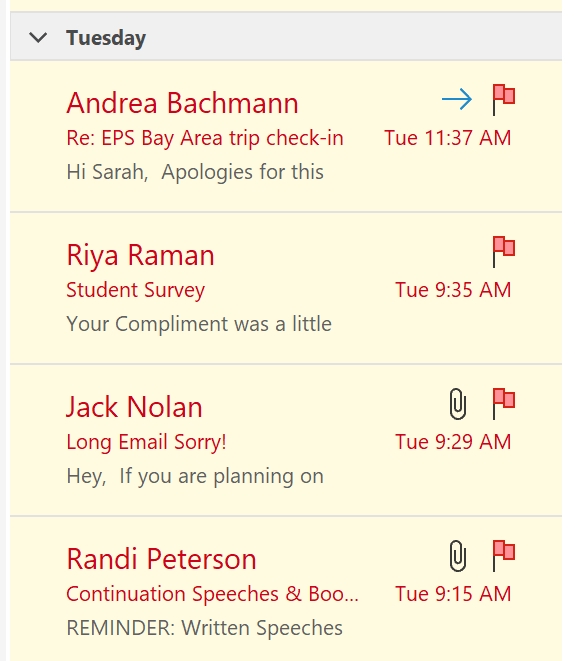

One Outlook feature I have found incredibly helpful in this process is the flag feature. If I only have time in the morning to briefly scan over my inbox, I will flag the items that I need to respond to first once I have the time. This helps me to prioritize which order to tackle my inbox in and ensures that emails from parents and students in particular are responded to in a timely manner.

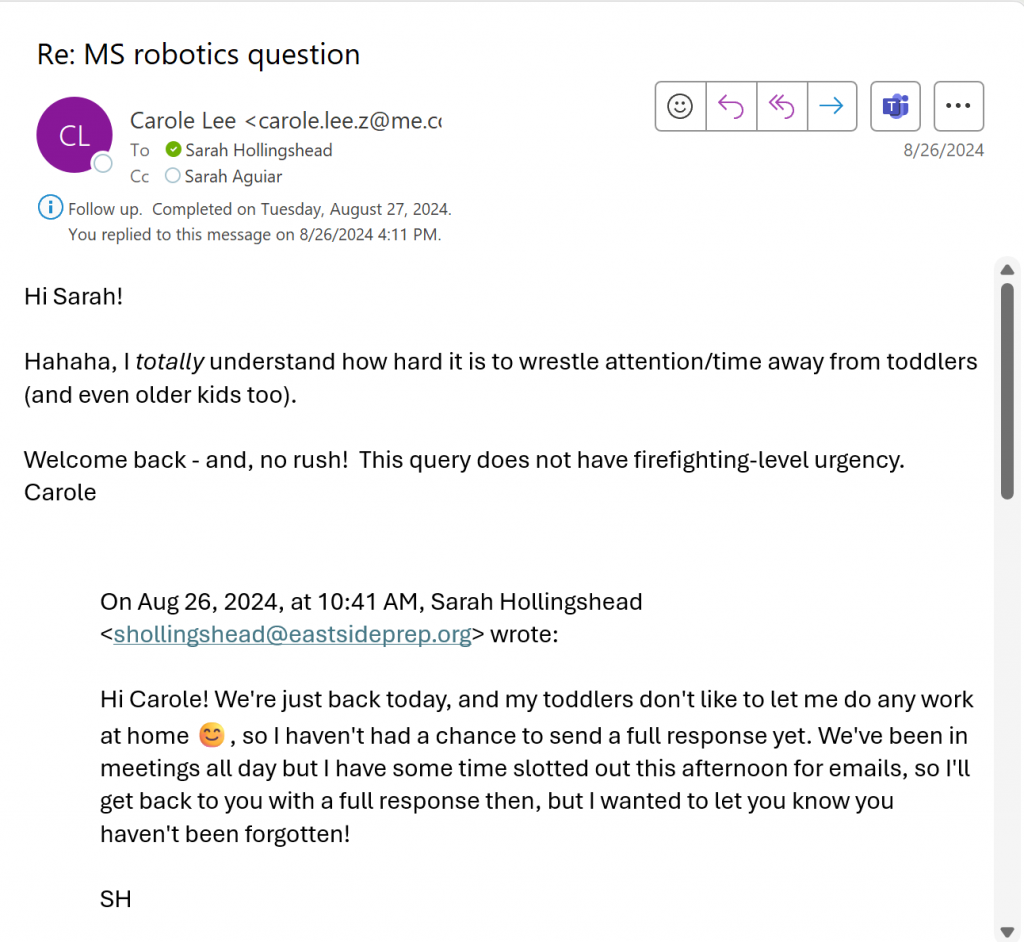

I typically am able to find 15-30 minutes in a day to manage my inbox, but there are some days that I need to delay this process until later in the week. However, it really bothers me when I have sent an email to someone and hear nothing in response, so I have also made it a practice to send a quick note to whomever I need to delay responding, letting them know that I have received their email and provide a timeline by which they can expect a response from me. An example of this is pictured below. I had received an email from a parent about the robotics team over the summer when I was on vacation and couldn’t respond. Once I was back on campus, I let her know that I had received the email and planned to respond later that afternoon when I had a free moment. You can also see from the timestamp that I kept my promise and responded later the same day.

Clear, timely communication is essential to building trust and maintaining strong relationships with students, families, and colleagues. By setting clear expectations, developing sustainable routines, and using tools like Outlook flags, I’ve created a communication system that works within the realities of my personal and professional life. Even when I can’t respond immediately, I make it a priority to acknowledge messages and provide a clear timeline for follow-up—demonstrating respect for others’ time and modeling professional communication habits.

(3) Displays openness and comfort with visitors observing class; seeks out diverse opinions of others for guidance

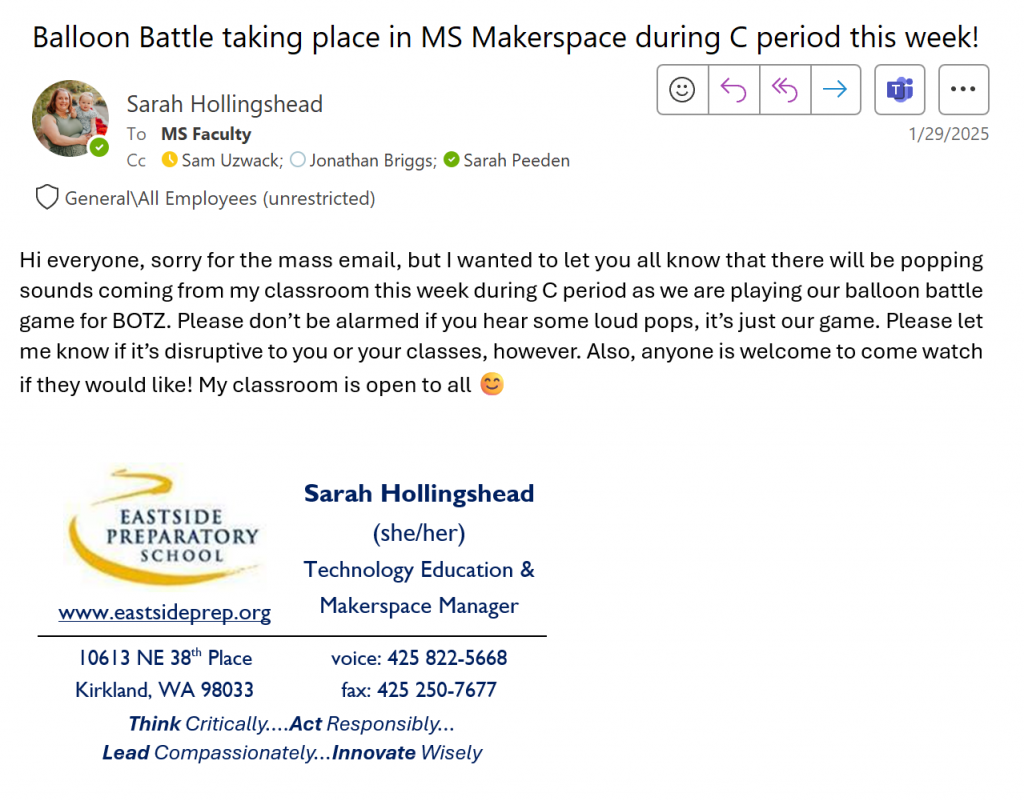

My classroom door is almost always open and I really love having visitors! The activities I do in my classes and during open makerspace time are engaging and fun to watch, so I also invite others in to see what’s happening in MS-107 and 108.

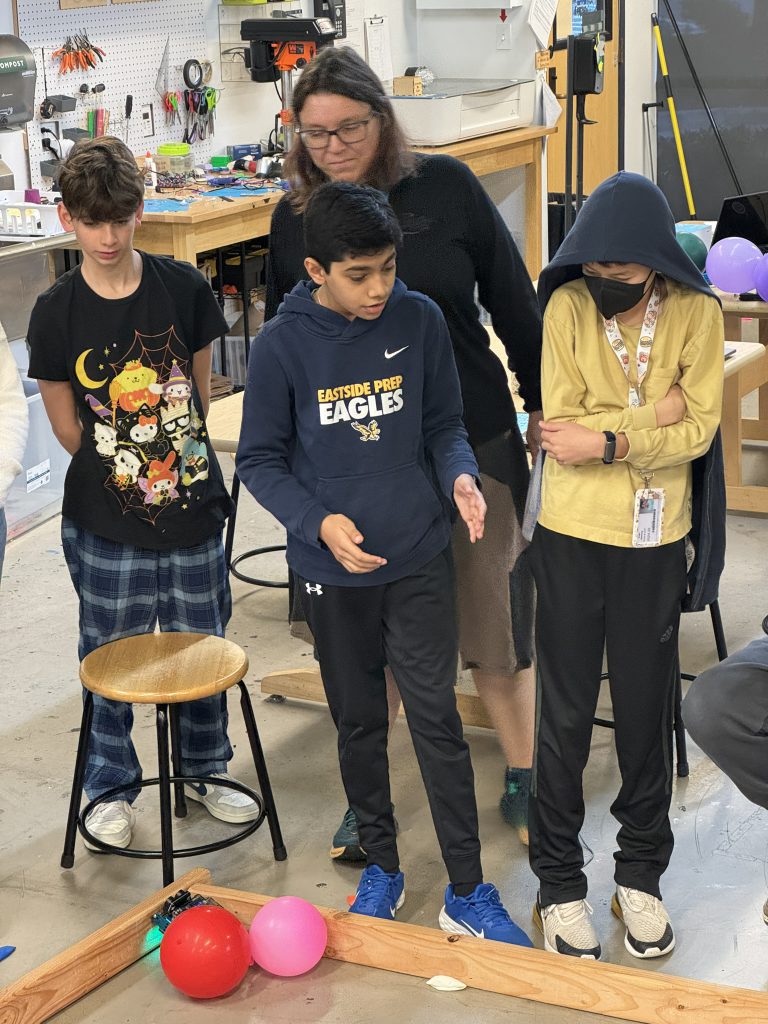

Sam Uzwack and Jonathan Briggs have accepted this invite on several occasions, and in fall of this school year, Dr. K came in to watch the Balloon Battle as well.

Occasionally, I need volunteers to participate in the activities we’re doing, and having the teacher office next door in the newly-configured middle school has been an easy way for me to invite others in. In the fall of this school year, my MAKE class built devices to deliver candy to trick-or-treaters in a creative and socially-distanced manner. I thought it would be more fun for students to show off their devices with real trick-or-treaters, but I didn’t have time to get other students involved. So, I wandered next door with my request and Malcolm and Wink obliged. Malcolm even innovated wisely with a quick costume!

In addition to faculty and staff visiting, my classroom doors are also open to visitors who are touring the school for a variety of reasons. This can be students and parents who are checking out the school during application season or groups of teachers and staff from other schools who JB typically brings around my space to see what we’re doing for our engineering and maker curriculum. I’ve even had some very cute visitors that are checking out their options for middle school very early in their educational career.

The second part of this indicator—seeking out the diverse opinions of others—has been challenging for me in the past. I take pride in my work and value being seen as competent, which can make receiving feedback—especially unsolicited advice—feel difficult and at times trigger defensiveness. However, this is an area I’ve been intentionally working to grow in. I recognize that my peers and colleagues bring unique strengths and perspectives to teaching, and that their approaches often differ from mine. By staying open to their insights, I’ve come to see these differences as valuable learning opportunities rather than critiques.

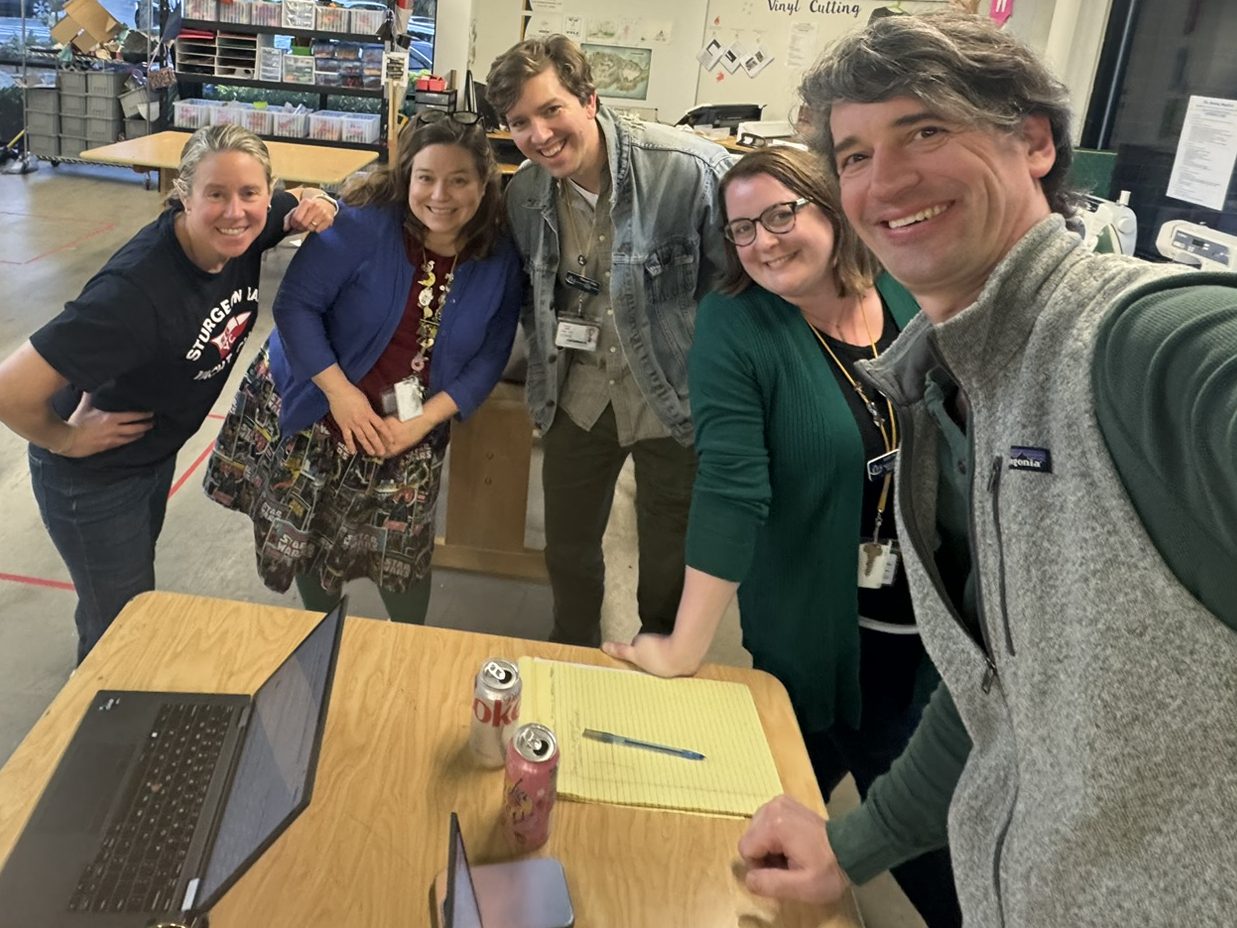

The PDP process has pushed me to grow in this area. When I was asked who I wanted on my team, I sought out those who teach in different disciplines than mine, with the aim of receiving feedback focused on my instructional practice instead of on the specific content that I teach. My wish was (mostly) granted and my team consisted of Katie and Elin, who teach science, and Malcolm, who teaches Spanish.

Examples of some of the helpful feedback these three have given me during and after their observations of my classes are below.

“I notice that you said, ‘Do you have any questions?’ when you were getting ready to transition the class to their work time. You might try to change the phrasing to, ‘What questions do you have for me?’ This was a recommendation that came to me from Sam Uzwack initially and can improve this part of our practice by communicating to the students that we not only welcome but also anticipate questions and (hopefully) makes them more willing to seek clarification from us.” – Katie Dodd after observing my BOTZ class

“I liked the method of putting the table to fill out as they planned their final MA in the OneNote. Filling out the different sections of the form is a good way to chunk-out the assignment and hold students accountable for each step of the project.” – Elin Kuffner, after observing my MAKE class

“I notice that students are sitting in self-selected groups, and they are 100% separated by gender. This may be leading, in part, to a lot of side chatter amongst the students while you are teaching. Some of the chatter is screen-sharing and helping each other through the process you are guiding them through, some is kids showing off what they’ve done to each other, and some, of course, is tomfoolery. Have you considered using a seating chart to break up the groups a bit and help with the side-chatter? I assign students into a different seating arrangement every class and find it helps with these classroom management and clique issues.” – Malcolm Yates after observing my WEB class

Jonathan was assigned as my leadership team member, which didn’t align with my initial request, as he is the head of the technology discipline. However, having him on my team has turned out to be a valuable and supportive addition and a welcome exception to my initial request. He brings a wealth of experience in both education and instructional practice. As the sole teacher of the middle school technology classes, it’s been helpful to have JB gain insight into the work I do in my “MS tech island” and provide feedback on how my courses align with the broader technology discipline. After observing my MAKE class, Jonathan offered insightful feedback—not only on my teaching strategies, but also on the lesson content, which that day focused on electronics and circuit boards (a topic in which JB has more expertise than I do). Some of the helpful feedback I received from him is noted below.

“I like the options this project offers students to engage with motors and circuits! You might consider adding some of these opportunities for students to expand their thinking:

- Servos are used exclusively for animatronics

- BIG servos are used for auto steering cars and building race simulators

- Servos are used for remote-controlled things (steering, plane flaps, etc.)

- Halloween decorations are often servo-driven (like the “Boo!” box you shared in your demo)

However, there was a trade-off between going for continuous servos vs using the time to recap what was learned about positional servos and tie this experience into thinking about a final project. In an ideal case, you’d want to squeeze the class slightly to allow for a few more minutes to wrap up at the end. Based on the constraints, though, the last 10 minutes was used very well.” – Jonathan Briggs after observing my MAKE class.

I have done my best to apply this feedback to my practice during the final trimester of the school year. For example, changing the way I pose questions to students—asking, “What questions do you have for me?” as Katie suggested—has led to more student inquiries before we begin assignments. I also created a seating chart for my 8th graders based on Malcolm’s recommendation, which resulted in more diverse and productive group work [you can read more about how I built this chart using suggestions from Sarah Peeden in section (4)]. I’ve continued using the planning document for MAKE as previously suggested, while also exploring more features in OneNote, such as to-do lists, to make the planning process more robust. Additionally, I’ve become more intentional about managing the end of class—limiting the introduction of new content in the final 10 minutes to allow time for review and setting up the next day’s goals, as JB advised. Through this process, I’ve also come to understand that feedback isn’t a judgment of my ability, but rather an opportunity to learn from others and continue improving my teaching practice.

These experiences through my PDP have helped me recognize the value of observing and learning from the practices of others. I reached out to Alicia Hale for support in using different features in Canvas and incorporating tools like FlipGrid into my classes. Initially, I was hesitant to use FlipGrid—it felt like just one more thing to manage—but it ultimately became an essential tool in my MAKE class. It allowed students to submit projects remotely and later continued to be useful once we returned to campus, giving me a digital record of their work without needing to store physical copies or worry about students taking them home. Alicia showed me how to use FlipGrid effectively and helped brainstorm ways to integrate it into my curriculum.

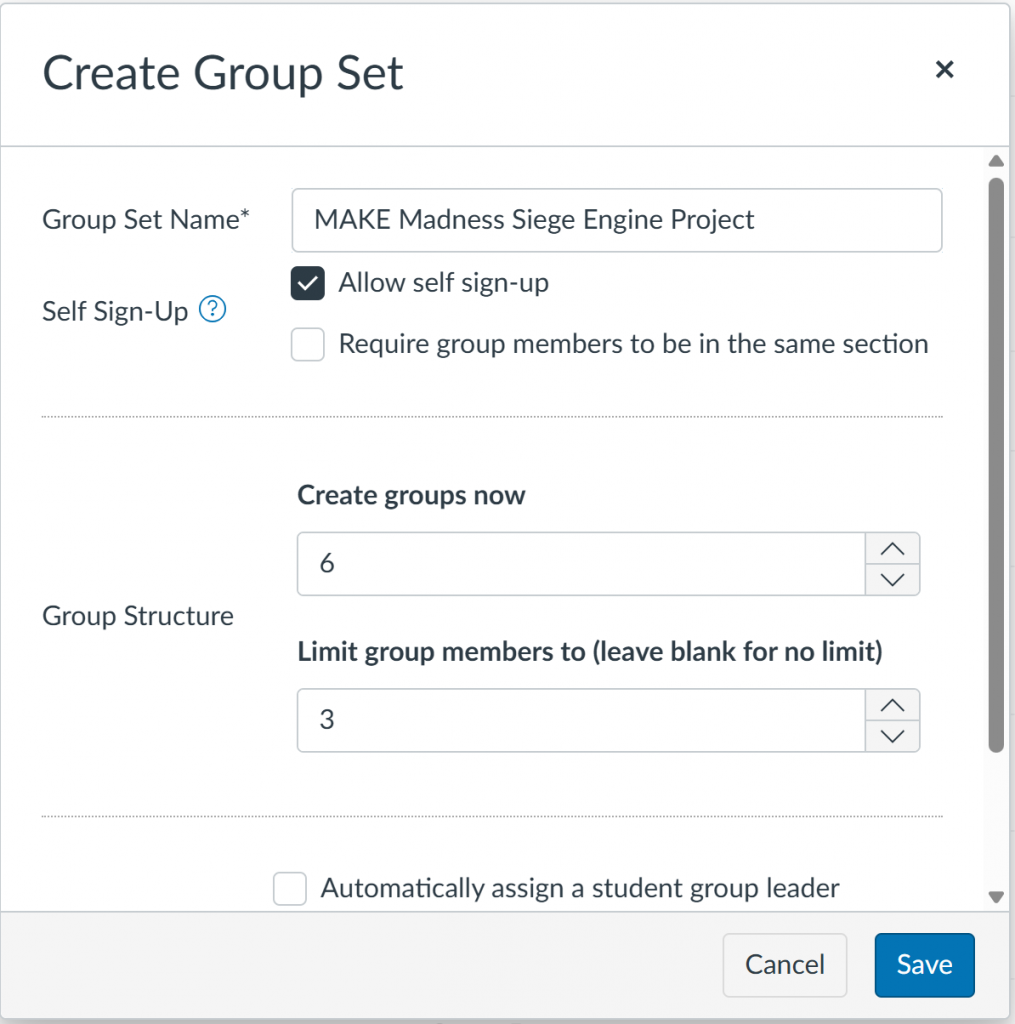

She also subbed for my MAKE class during spring trimester this year. On that day, students needed to organize themselves into project groups, but I hadn’t set up the groups in Canvas yet because they hadn’t made their selections. After class, Alicia debriefed with me and introduced a helpful Canvas feature that allows students to self-sign-up into groups. I can specify the number of groups and how many students per group, and Canvas handles the rest. Had I known about this earlier, it would have solved the issue of my absence entirely. I plan to use this feature in MAKE next year.

These experiences have deepened my belief that teaching is at its best when it is both shared and observed. Keeping my classroom open to visitors and actively seeking feedback from colleagues has not only enriched my own practice but also strengthened the learning experiences I provide for students. I now view collaboration and observation not as interruptions or evaluations, but as essential parts of growing as an educator.

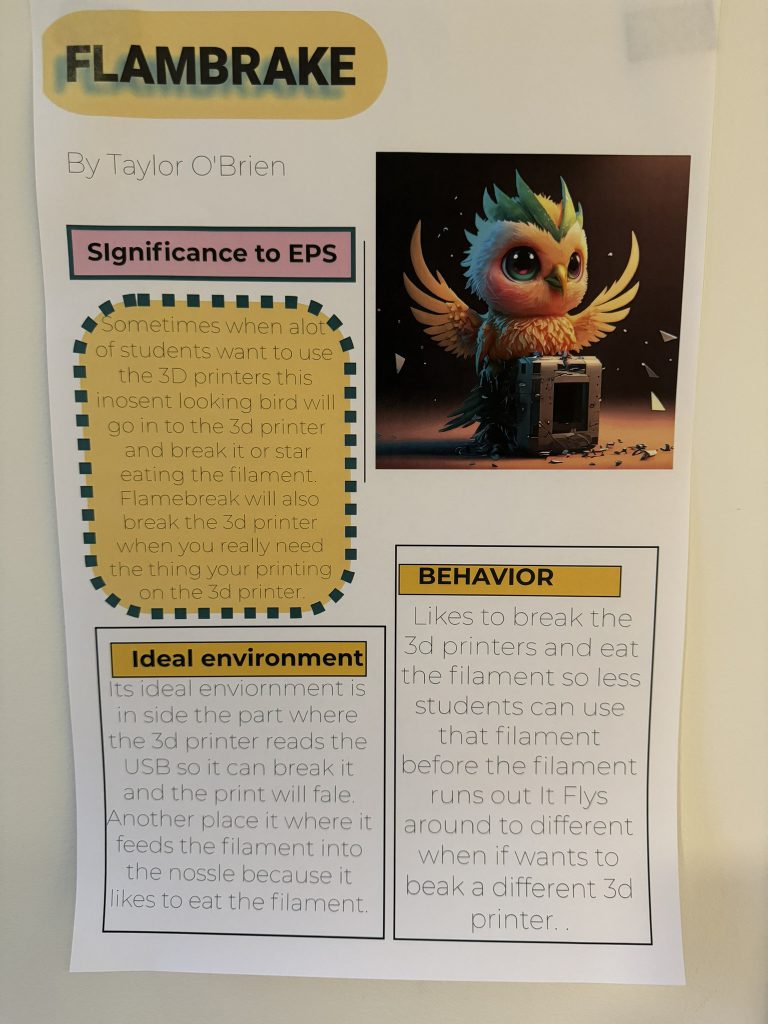

BONUS Evidence of another Alicia Hale tech integration win: She had students in LT1 use Adobe AI tools and taught them to craft a specific prompt to make photos of their creatures, many of which live in the MS Makerspace.

(4) Approaches recommendations for improvement receptively and responsively

Although I’ve historically felt some discomfort with peers observing and giving me feedback (as I discussed in the previous indicator), I actively welcome and seek out opportunities for my supervisors to observe my teaching and offer constructive insights. I especially value the experience and practical wisdom that Sarah Peeden brings—she has a deep well of strategies and best practices that I’m always eager to learn from. During a regularly scheduled observation on Friday, 2/7 of this school year, I asked Sarah to focus on some classroom management challenges I’d been facing in my WEB class so she could offer targeted feedback.

That term, I had several students who were already very familiar with web design. After conversations with them outside of class, we agreed that they could work independently during demonstrations—as long as they reviewed assignment posts and ensured their submitted projects included all required code and skills. However, I had allowed students to choose their own seats, and this group opted to crowd six students into a table built for four, despite my encouragement to spread out. This created both logistical and behavioral issues. It limited their own workspace and led to frequent side conversations that distracted students who were less experienced and needed to focus on the demo. The newer coders at that table were often pulled into discussions about the independent work, asking the advanced students to explain or teach them during the demo—which disrupted the flow of class and created distractions for everyone. In response, Sarah suggested I consider implementing a seating chart. I don’t usually use assigned seats in BOTZ or MAKE, where students are often up and moving around the room, but WEB involves more sitting—both for demos and hands-on coding work—so a structured seating plan made sense in this context.

I didn’t want to randomly assign seats, as I wanted students to have some sense of ownership and autonomy in the process. Sarah suggested I try a tool called the Innovation Code—a card game that could help guide intentional groupings while still giving students agency.

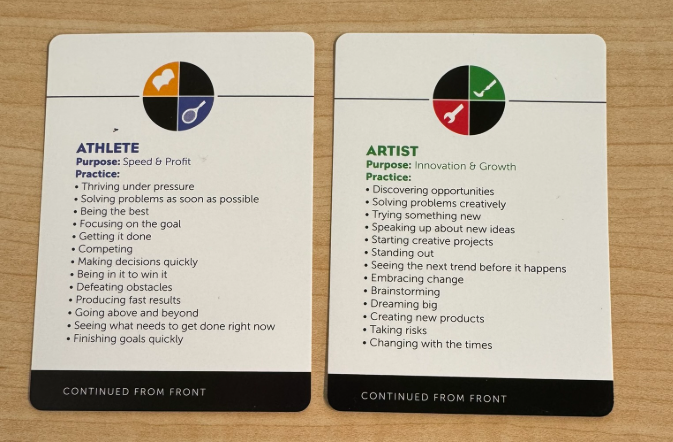

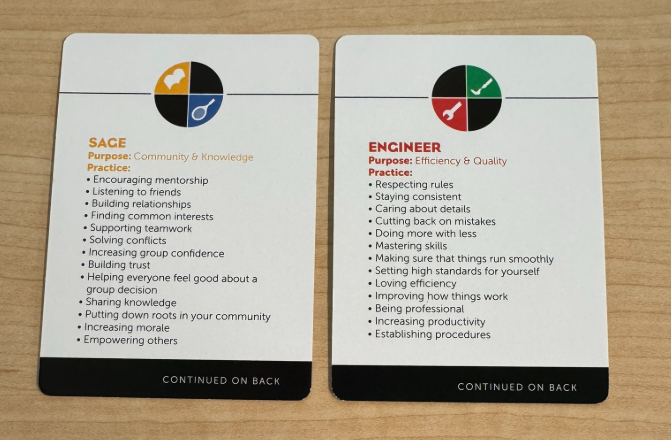

The card game is based on a book of the same name, which asks people to look through different personality traits or skills and pick the ones that speak to them the most. The cards are color-coded for a specific worldview (Artist, Athlete, Engineer, and Sage) that we use to approach innovation.

The goal is for individuals to identify their own worldview and then form groups composed of people with differing perspectives. Ideally, this results in teams that bring together a range of personalities and strengths, encouraging collaboration on projects that benefit from diverse viewpoints. The ultimate aim is to produce work that reflects a broader range of perspectives and skills.

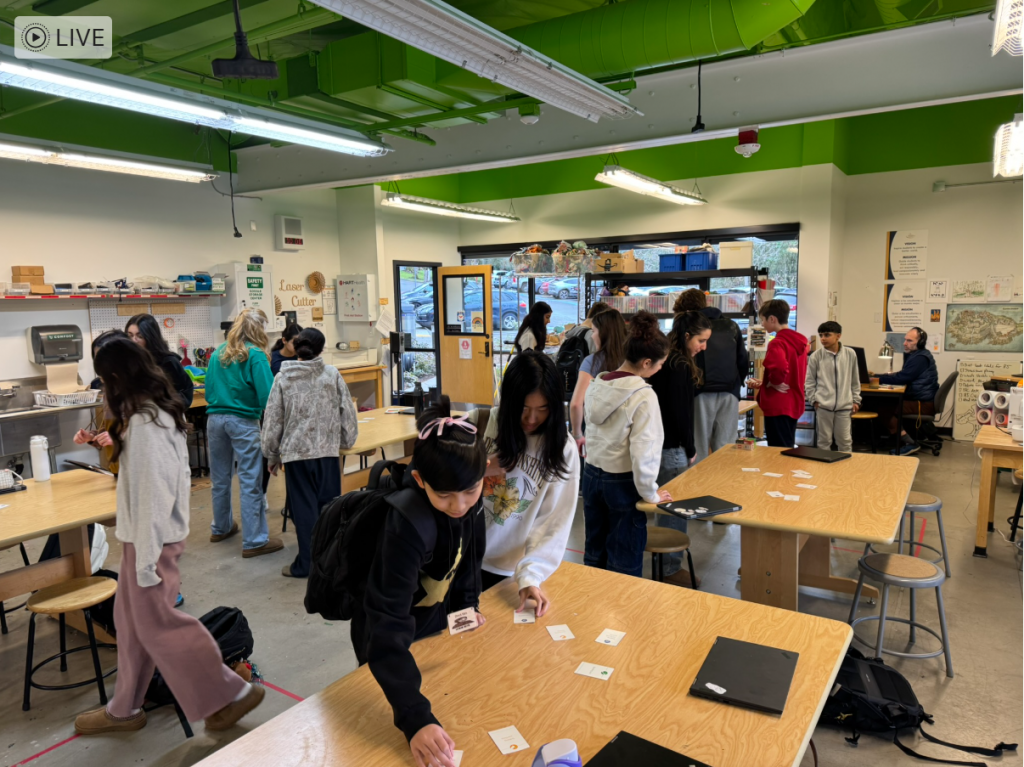

I implemented this activity in my spring trimester class as a way to build my seating chart. First, I spread all the cards out on the classroom tables and instructed students to walk around and read them. After reviewing the cards, students were asked to select two to three that they felt were personally relevant. From those, they chose the one that resonated most with them. Then, students grouped themselves based on the color of the trait on their chosen card. Within these groups, they discussed why they selected their card, how it represented them, and looked for commonalities among their group members.

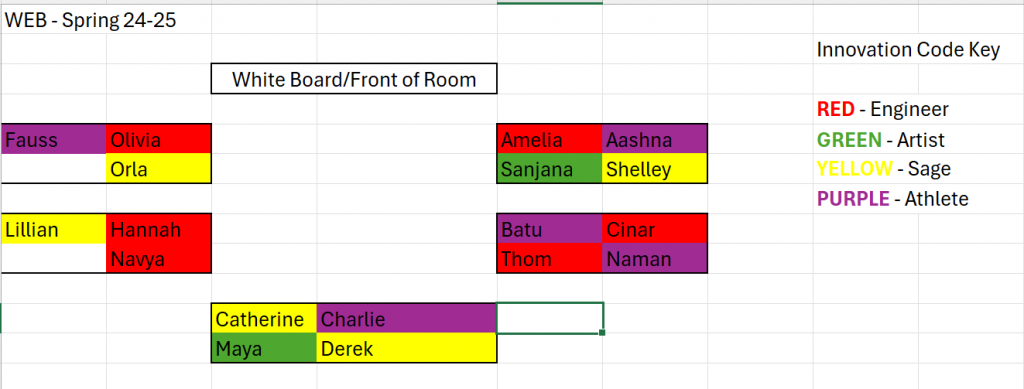

After the discussion in their groups, we talked about how it can be beneficial to have people from each of these worldviews work together on a team. For example, the Engineer cares about the details of a project, but can sometimes focus more on those at the sacrifice of finishing the project. So an Athlete would be a good partner to keep the Engineer on task because they care about getting things done and moving on. A Sage would help to resolve any conflict that may arise between the Engineer and the Athlete because they want to make sure everyone feels good about a group decision, and the Artist could assist in the process by coming up with creative solutions that everyone could work towards. Once students understood the strengths and weaknesses of their group and could describe how the different groups could work well together, I let them self-select into table groups, with the understanding that this would be who they would work with for the first group project and they had to make up the groups so (ideally) each worldview was represented. This was a bit challenging given that there were only 2 people who identified themselves as the Artist, but the groups are working well so far.

This process has helped me see the benefits of assigning seats for behavior management, and I appreciated the creative manner Sarah suggested I use to do it. I also appreciated how it still provided some form of choice on the part of the students as they self-selected into their groups.

This experience reinforced the value of approaching feedback with openness and adaptability. By receptively incorporating Sarah’s recommendations, I was able to address classroom management challenges in a way that honored student autonomy while fostering a more productive learning environment. It also highlighted the importance of collaboration—not only among students but between educators and mentors—in continually refining my teaching practice. Moving forward, I am committed to maintaining this responsive mindset to support both my professional growth and my students’ success.